For much of the past two centuries, it was illegal to be gay in a vast swathe of the world - thanks to colonial Britain.

Till today, colonial-era laws that ban homosexuality continue to exist in former British territories including parts of Africa and Oceania.

But it is in Asia where they have had a significantly widespread impact. This is the region where, before India legalised homosexual sex in 2018, at least one billion people lived with anti-LGBTQ legislation.

It can be traced back to one particular law first conceptualised in India, and one man's mission to "modernise" the colony.

'Exotic, mystical Orient'

Currently, it is illegal to be gay in around 69 countries, nearly two-thirds of which were under some form of British control at one point of time.

This is no coincidence, according to Enze Han and Joseph O'Mahoney, who wrote the book British Colonialism and the Criminalization of Homosexuality.

Dr Han told the BBC that British rulers introduced such laws because of a "Victorian, Christian puritanical concept of sex".

"They wanted to protect innocent British soldiers from the 'exotic, mystical Orient' - there was this very orientalised view of Asia and the Middle East that they were overly erotic."

"They thought if there were no regulations, the soldiers would be easily led astray."

While there were several criminal codes used across British colonies around the world, in Asia one particular set of laws was used prominently - the Indian Penal Code (IPC) drawn up by British historian Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay, which came into force in 1862.

It contained section 377, which stated that "whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal" would be punished with imprisonment or fines.

Lord Macaulay,who modelled the section on Britain's 16th Century Buggery Act believed the IPC was a "blessing" for India as it would "modernise" its society, according to Dr Han and Dr O'Mahoney's book.

The British went on to use the IPC as the basis for criminal law codes in many other territories they controlled.

Till today, 377 continues to exist in various forms in several former colonies in Asia such as Pakistan, Singapore, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Brunei, Myanmar and Sri Lanka.

Penalties range from two to 20 years in prison. In places with Muslim-majority populations which also have sharia law, LGBT persons can also face more severe punishment such as flogging.

Lasting legacy

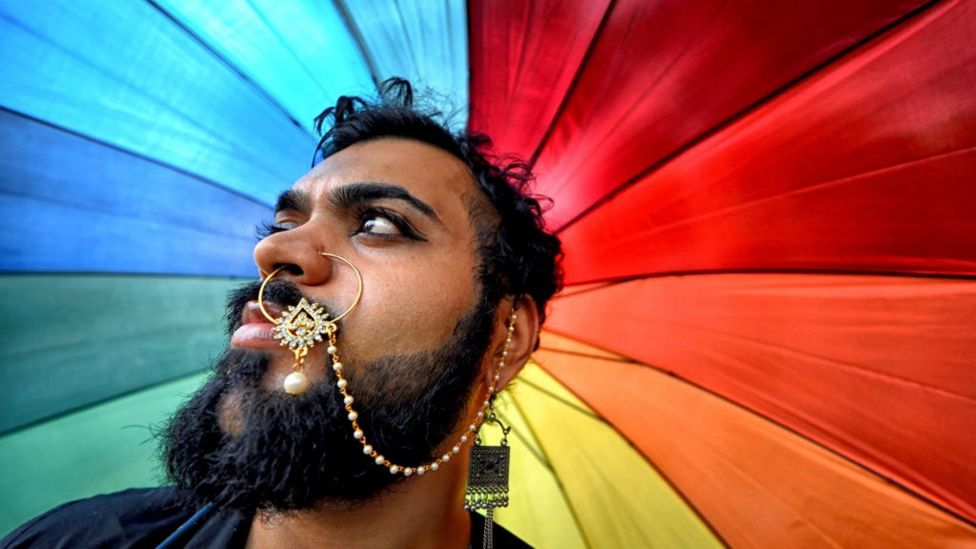

Activists say these laws have left a damaging legacy on these countries, some of which have long had flexible attitudes towards LGBTQ people.

Transgenderism, intersex identity and the third gender, for example, have traditionally been a part of South Asian culture with the hijra or eunuch communities.

In India, where for centuries LGBTQ relationships were featured in literature, myths and Hindu temple art, present-day attitudes now largely skew conservative.

"It's in our traditions. But now we are getting so embarrassed about [LGBTQ relations]. Clearly the change happened because of certain influences," says Anjali Gopalan, executive director of Naz Foundation India, a non-governmental organisation which offers counselling services for the LGBTQ community.

One common argument governments have made for keeping the law is that it continues to reflect the conservative stance of their societies. Some, like India, have even ironically argued that it keeps out "Western influence".

But activists point out that this perpetuates discrimination and goes against some countries' constitutions which promise equal rights to all citizens.

This has a "de-humanising effect" on an LGBTQ person, and can seriously impact their access to education and career opportunities as well as increase their risk of poverty and physical violence, said Jessica Stern, executive director of LGBTQ rights group OutRight International.

"If you're a walking criminal, you're living with a burden every day. Whether you internalise it or not, it affects you and everyone who loves you," she told the BBC.